Overview

The report examines the drivers of the growth in poor mental health among 14 to 24-year-olds in England.

Previous efforts to understand the causes of young people’s declining mental health have often focused on examining drivers in isolation or offering only narrative summaries.

Our approach goes significantly further by systematically evaluating multiple theories in parallel, using a combination of data analysis and literature review. We describe specific theories for the trends and assess the strength of evidence supporting each one, highlighting where important gaps remain.

- Executive summary

- Background

- Aim of report

- Trends in young people’s mental health

- Theories for trends in young people’s mental health

- Evaluating theories using existing evidence

- Theory evaluation insights

- Conclusions

- References

Key insights

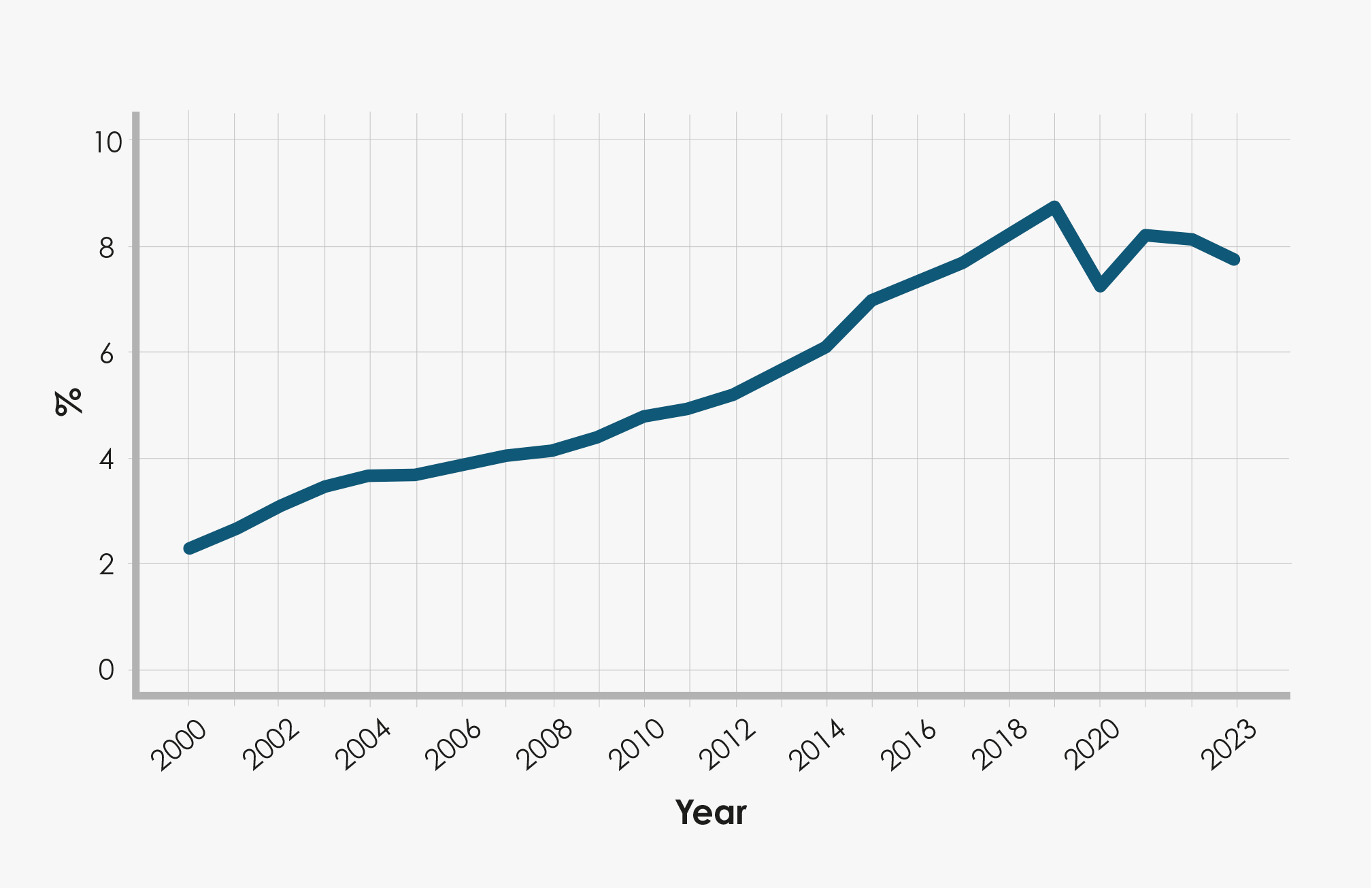

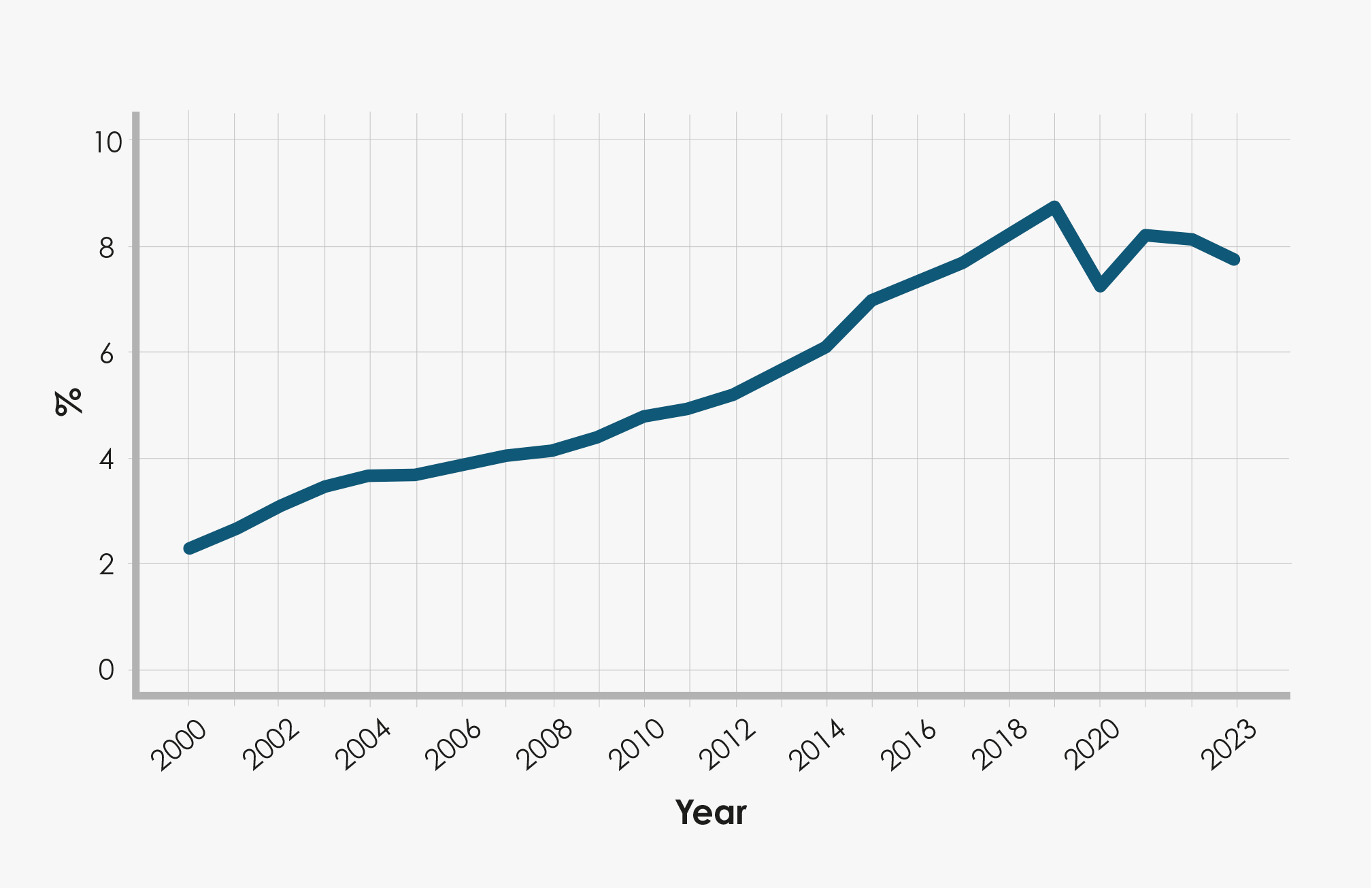

Mental health symptoms among young people increased substantially from around 2010-2012, particularly low mood and anxiety.

Proportion of young people aged 14 to 24 years in England with a presentation to primary care for a mental health problem.

Out of ten theories considered, several emerged as likely contributors to these trends:

- worsening sleep quality

- employment precarity and affordability pressures

- social media and smartphone use

- reduction in children and youth services

The study provides further evidence that the increase in presentations of young people with a mental health problem (or decline in young people’s mental health) is real – and not merely a result of increased symptom recognition, greater awareness, overdiagnosis, or reduced resilience.

Child poverty and discrimination affect young people’s mental health, but their levels have not changed enough over time to explain the decline in mental health.

A structured approach was developed to evaluate ten theories that might help explain changes in youth mental health.

This involved:

- Refining a list of commonly cited theories drawing on input from cross-disciplinary experts

- Exploring the theories in depth

- Examining available evidence of change over time in the relevant factors

- Identifying systematic reviews to scope evidence, prioritising stronger study designs

- Considering subgroup effects in available evidence in relation to broader findings

Information was then synthesised and triangulated with new data analysis to support pragmatic conclusions and highlight remaining gaps and complexities in understanding.

Trends in youth mental health were analysed using nationally representative survey data (Understanding Society) alongside primary care records (Clinical Practice Research Datalink).

Statistical analysis enabled the examination of changes by mental health condition and by subgroups such as gender, ethnicity, region, and deprivation level. Analyses also explored whether young people have become more likely to report symptoms at lower thresholds, and whether there have been changes in levels of resilience over time.

For full details of methodology and approach, read the accompanying technical report.

Implications

This research has made an important foundational start in plugging the missing evidence gap. We very much hope these insights will spur further investigation and start to enable better integrated public policy and practice solutions for young people.

There are several areas where evidence remains too limited or inconsistent to draw firm conclusions about drivers of youth mental health trends. Key gaps include how factors such as academic pressure, discrimination, environmental concerns, and risk aversion have changed over time, as well as how they causally influence mental health.

Some well-researched areas like social media use are constrained by weak study designs. Improved data collection and more robust research, including randomised trials and policy evaluations, are needed.

Further investigation into subgroup differences (e.g. by gender and ethnicity) and cross-national comparisons could also provide valuable insights.

Many influencing factors appear to operate through shared mechanisms such as stress, social comparison, and uncertainty, suggesting that future work should also focus on these underlying pathways.

The research further reinforces the need for mental health to be prioritised and for preventative solutions that bring together health services, education, employers, civil society and other stakeholders. Investment in young people’s mental health should continue to focus on prevention and early intervention.

Proportion of young people aged 14 to 24 years in England with a presentation to primary care for a mental health problem.

Proportion of young people aged 14 to 24 years in England with a presentation to primary care for a mental health problem.