As 2022 draws to a close, Andrea Barry, our Analysis Manager and Zach Wilson, our Senior Analysis Officer, reflect on current trends in youth unemployment.

Economic inactivity in young men on the rise

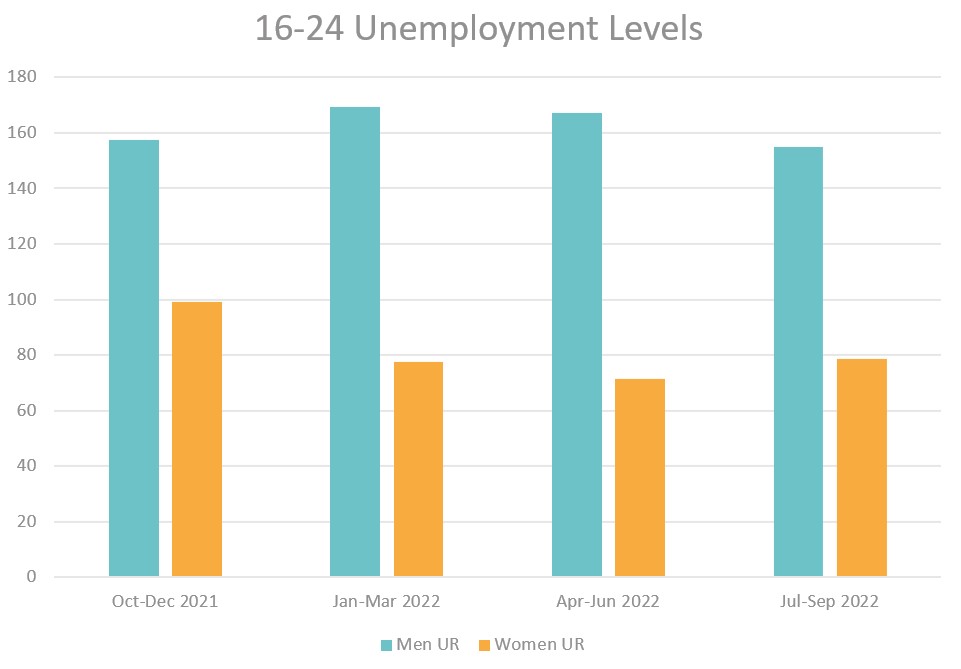

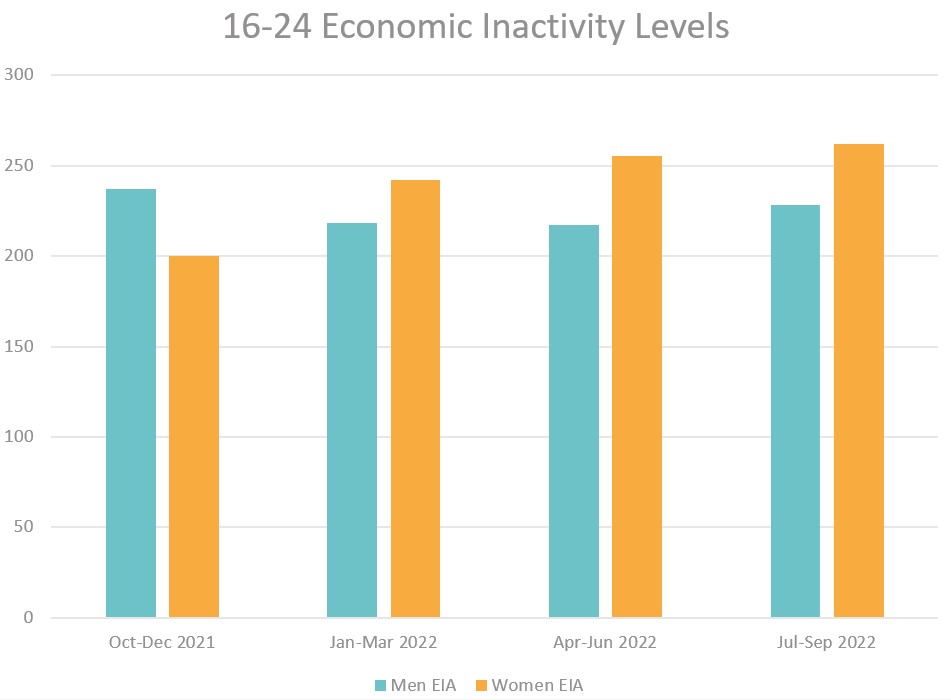

Over the last quarter, economic inactivity for young women aged 16-24 who are not in full-time education decreased slightly, from 19.5% to 18.3%, however the unemployment rate went up to 7.2% from 5.5%, but the employment rate decreased, going from 76% to 75.8%.

With respect to young men not in full time education, in the last quarter, economic inactivity rose from 14.1% to 16.7%. The unemployment and employment rates for these young men went from 9.5% to 11.5% and 77.8 to 73.7%, respectively, in the last quarter.

This is not a good picture for young men not in full-time education that have left the labour market, as it shows less are seeking work. By contrast, for young women, more are entering the labour market but the employment rate has still decreased. Therefore, more women are unemployed and more men are unemployed or economically inactive.

Economic inactivity continues to be a significant story for young people, but especially young women who are not in full time education. There’s a higher level of young women who are economically inactive compared to men, and the number continues to rise. This new ternd of more young women who are not in full time education being economically inactive is concerning, especially given the reason for the inactivity.

Long-term sickness

Most individuals across all groups were inactive before reporting inactivity due to long-term sickness. In other words, they had already been out of the labour market but for different reasons. For young people, the large flow is from inactivity due to education to inactivity due to long-term sickness, which will include a physical or mental illness. Additionally, when someone exits the state of being long-term sick, they return to being inactive for a different reason. Amongst sectors, some were overrepresented, such as retail, for long term sick inactivity. However, individuals who experienced long-term sickness inactivity whilst working in retail had previously held positions in social work and health care. Those who had previously worked in the fields of health and social work had greater rates of long-term sickness than those who had not. Moreover, low paid occupations were more represented among the long-term sick. These occupations and sectors have an overwhelming number of young people in work, and thus this link between sectors/occupations and low paid work with long term sickness needs to be addressed fully.

Not in education, employment or training (NEET)

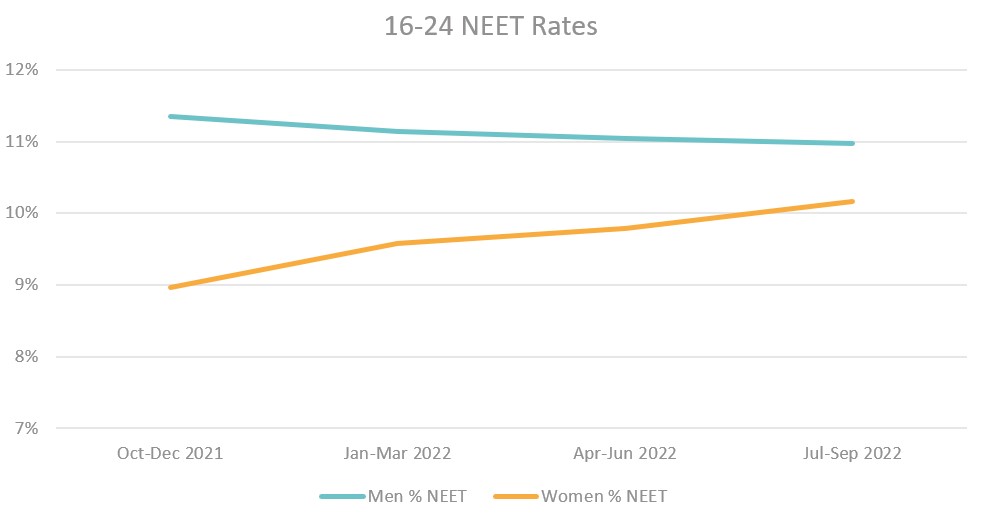

The number of young people who are not in employment, full-time education, or training (NEET) has risen to 922,000. This is troubling as the NEET level hasn’t been this high since February-April 2021. 69% of this group are inactive (not in working and not looking/unable to work) and 31% are unemployed (not in work and looking to work).

Although economic inactivity for young women has decreased in the last quarter, NEET rates for young women are increasing, which means the rates are converging to those of young men. NEET rates for young men are decreasing at a much slower rate than NEET rates are increasing for young women. Risk factors for NEETs, given the alarming rise for young women, needs to be monitored and explored more fully in the New Year. Combining an alarming rise of NEET rates for women and increased unemployment for women who are not in full time education, the cost of living crisis is clearly biting certain groups of young people harder.

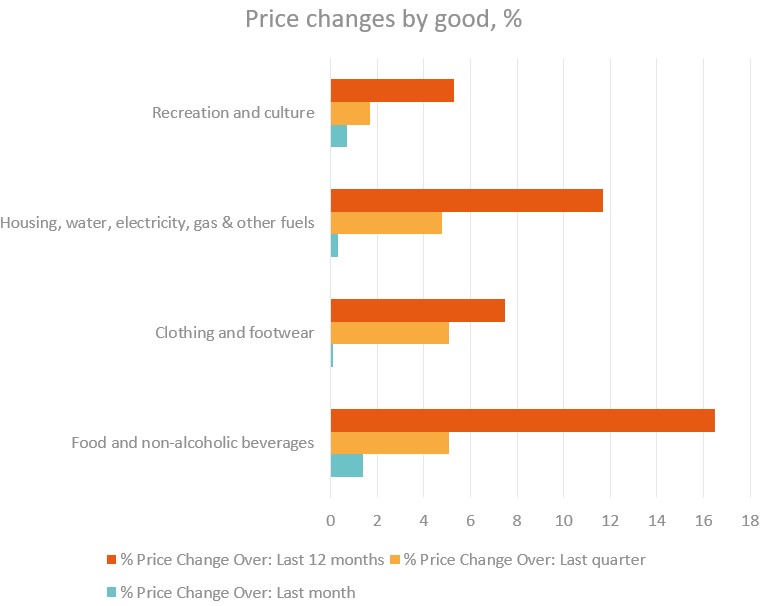

Cost of living and heads of household

Food prices continue to rise, as well as those for clothing and footwear. Although they’re smaller % over the last month, it is still a larger price increase than other items like electricity, housing, and clothing. Prices in each category have increased significantly over the last 12 months.

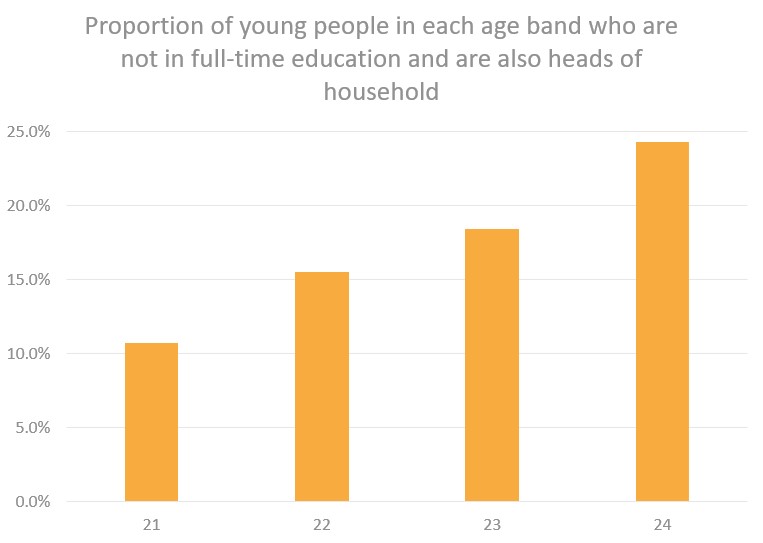

Like many other groups, young people have not experienced a nominal increase in pay, and thus the increase in inflation contributes to a real wage cut for this group. This will be most urgent for young people who are HoH or in receipt of benefits.

Source: YFF analysis of ONS, Labour Force Survey (July-September 2022)

It should be reiterated that there needs to be urgent policy focus on young people who are ‘heads of household’, especially those with other risk factors for being hit harder by rising costs, such as a disability, an ethnic minority background, and NEET status – which was highlighted earlier. On a positive note, the government has decided to increase benefits in line with inflation, from April 2023. With this, those young people who are recipients may find that it helps to lessen the blow. However, it will be a long holiday period for young people who find themselves at the head of household, not in full time education, struggling with rising prices of the basics, and looking for work. We must continue to address the very polarised labour market for young people not in full time education, as well as a comprehensive response to the cost of living crisis for all young people.