Today’s ONS job statistics show that, on the face of it, it’s a relatively good labour market release for the government. There is a small decline in the economic inactivity rate for 16–17-year-old men, and a small increase for the 16–17-year-old women. For 18-24 men, there is a small increase for the women and a decline for the men. These increases and declines are relatively small, and combined with a decline in claimant counts, this is a good sign for young people returning to work or education.

However, unemployment has increased for 16–17-year-olds not in full-time education who are also unemployed or economically inactive. There is also a similar decline for 18–24-year-olds who are not in full-time education. For those in full-time education, there is a substantial increase in employment.

It is particularly worrying that young people who are not in full-time education are increasingly further from the labour market. This risks a polarisation amongst young people, between those in education and those out of education. It’s important to understand why there is this detachment given the large vacancies in sectors where historically large numbers of young people are employed.

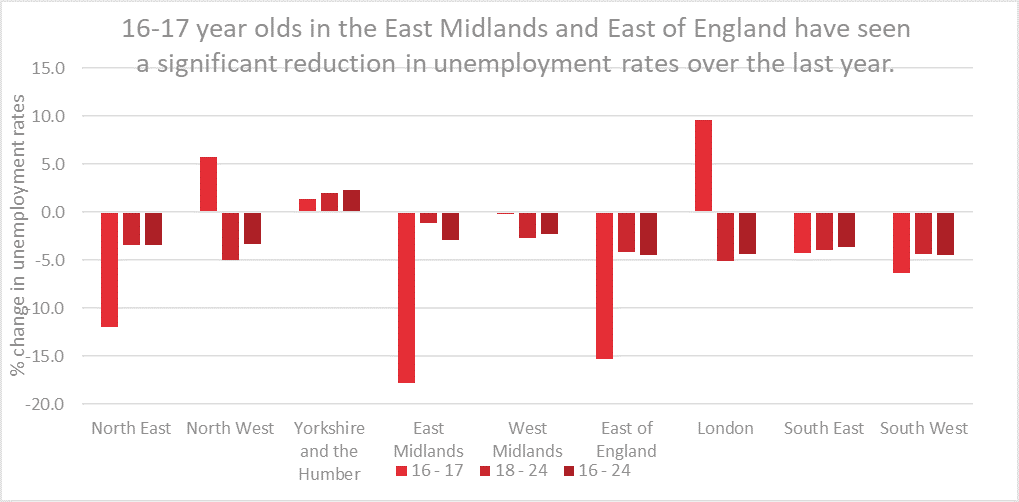

Regionally, there are significant differences in how young people have fared. Over the last year, the only region to experience an increase in unemployment rates for all young people 16-24 is Yorkshire and the Humber. Young people aged 16-17 in London and the North West have also experienced an increase in unemployment rates. Given the overall picture of inactivity increasing for young people out of education, it will be important to understand how these continue to play out in different regions.

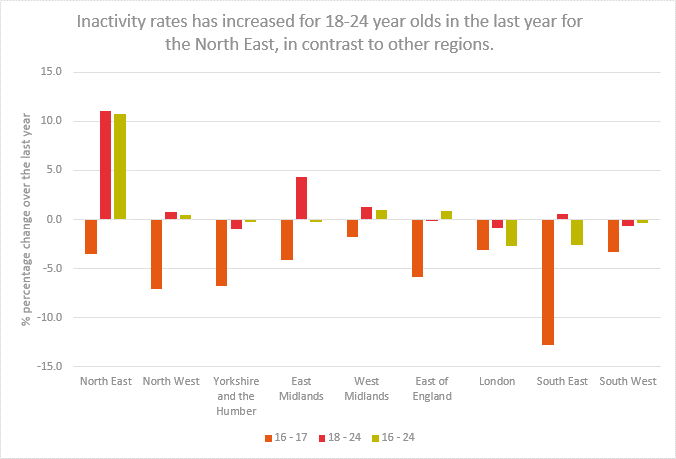

Similarly, inactivity rates have increased for 18–24-year-olds in the North East, in stark contrast to other regions in 2021. Again, regionally inequalities for young people need to be addressed, as this is a further risk of divergence between young people throughout England.